JUDGMENT

V. Kameswar Rao, J.- This petition has been filed with the following prayers:

“a. quashing the impugned order dated 18.07.2025 passed by Respondent No. 1; and

b. releasing the Gold (Coins) and jewellery seized in terms of Annexures B-1, B-2, J-1, J-2, J-3 & J-4 [Annexure C to the present writ petition]; and/or”

2. This present petition is a second round of litigation before this Court. The petitioners no. 1 and 2 are husband and wife and the petitioners no. 3 and 4 are their children. The brief factual background surrounding the case is that the petitioners herein, were subjected to a search and seizure operation at their residence which was conducted by the respondent/Revenue from 09.10.2024 to 11.10.2024, based on a search warrant authorized by the respondent no.3 under Section 132 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 (the Act).

3. During the search, the following gold and jewellery were seized by the Revenue:

| i. | | Gold (coins etc.) – 104 Grams; |

| ii. | | Jewellery – 4,808 Grams approx. being the value/weight based on the converted gold weight while the actual net weight is 2,519 Grams; |

| iii. | | The total value of the jewellery found was Rs. 5,39,76,316/- out of which jewellery amounting to Rs.1,51,16,209/- was released and the seizure was of Rs. 3,88,60,107/-. |

4. Ms. Kavita Jha, learned Senior Advocate appearing for the petitioners herein, stated that the search and seizure were illegal. As per her, the petitioner no.1, for and on behalf of himself and the rest of the petitioners addressed a letter to the department dated 25.11.2024 submitting the documents and pointing out that all the seized gold/jewellery was disclosed by the petitioners in their respective Income Tax Returns (ITR) and Wealth Tax Returns (WTR). She stated that as per the second proviso to Section 132 B(1)(i) of the Act, it was incumbent upon the respondents to release the seized gold/jewellery within 120 days from the date of search. Due to inaction on the part of the respondents, the petitioners filed another letter on 23.01.2025, reiterating their request for the release of the gold/jewellery along with reconciliation, demonstrating that each item mentioned in the Panchnama was duly disclosed by the petitioners in their returns.

5. She stated that as per the statute, when the person concerned makes an application within 30 days from the end of the month in which assets were seized and furnishes explanation to the satisfaction of the Assessing Officer, (AO) subject to the existing liability, the assets may be released. It is her submission that since the last date of search was 11.10.2024, and the application was filed by the petitioners under Section 132B on 25.11.2024, the requirement of the first proviso to Section 132B was met. She stated that even after the lapse of 120 days, no action was taken by the respondents and the documents placed on record by the petitioners were completely ignored. Thereafter, aggrieved by the same, the petitioners filed a writ petition before this Court being Rajesh Gupta v. Dy. CIT [W. P. (C) 2938 of 2025, dated 7-7-2025] She drew our attention to the order passed therein dated 07.07.25 which reads as under:

“3. The learned counsel appearing for the Revenue now submits that the Petitioners’ Application for release of the jewellery in question would be decided within a period of 1 (one) week from date. The Respondents are bound down to the said statement. The aforesaid statement also addresses the Petitioners’ second prayer in the present Petition.

4. In view of the above, no further orders are required to be passed in this Petition. The same is disposed of.

5. It is clarified that all rights and contentions of the Petitioners are reserved, and in the event the order passed by the Respondents is adverse to the Petitioners, the Petitioners would not be precluded from availing their remedies to assail the same including on the grounds as set out in the present Petition.”

6. It is her submission that bound by this order, it was incumbent upon the Revenue to pass the order deciding their application within the specified period as undertaken before this Court. However, the impugned order was passed only on 18.07.2025, 11 days after the date of the order of this Court, dismissing the application filed by the petitioners under section 132B of the Act and rejecting the release of jewellery/gold on completely perverse and frivolous grounds.

7. It is her submission that the impugned order is bad in law as the same has been passed by completely disregarding the fact that all the seized gold/jewellery has been duly disclosed by the petitioners in their respective ITRs/WTRs. The petitioners are regular and compliant income tax assessees under the Act. She stated during the search and seizure operation, the Revenue Officials gathered and seized all the jewellery/gold ornaments from the respective bedrooms of the petitioners despite them categorically pointing out to the Officials that the jewellery/gold is part of their disclosed incomes:

| i. | | WTRs filed by the petitioners and the earlier HUF’s; |

| ii. | | Jewellery Valuation Report obtained from time to time by the petitioners, jointly and severally; |

| iii. | | ITRs for different assessment years filed by the petitioners. |

8. As per her, the seizure is in contravention of the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) Letter F.No.286/26/82-IT(Inv.)-III dated 23.11.1982 which provides as under:

“.in the cases of persons assessed to wealth-tax the question whether there should be a seizure or not should be decided with reference to the actual jewellery disclosed for wealth-tax purposes.”

9. As per her, the Revenue had wrongly relied on the CBDT Instruction No. F.No.299/06/2023-Dir(Inv-iii) dated 16.10.2023, on the assumption that this instruction is applicable to future liabilities, which may/may not arise pursuant to the assessment proceedings. However, she stated, paragraph 3 of this instruction itself provides that assets can be released if the AO is satisfied that the nature and source of this jewellery is explained. In such a case, the Revenue’s approach to illegally hold the assets to be adjusted against future liabilities, is high handed. The respondents have arbitrarily attempted to justify this seizure, which is non-est.

10. She also placed reliance on the CBDT instruction No. 1916 of 1994, dated 11.05.1994, which has laid down guidelines for the ‘seizure’ of the jewellery found in the course of search. The relevant extracts of the said Instruction are reproduced hereunder:

“”INSTRUCTION NO: 1916 DATE OF ISSUE: 11/5/1994

Instances of seizure of jewellery of small quantity in the course of operations under Section 132 have come to the notice of the Board.

The question ofa common approach to situations where search parties come across items of jewellery, has been examined by the Board and following guidelines are issued for strict compliance:

(i) In the case of a wealth-tax assessee, gold jewellery and ornaments found in excess of the gross weight declared in the wealth-tax return only need be seized.

(ii) In the case of a person not assessed to wealth-tax, gold jewellery and ornaments to the extent of 500 gms. per married lady, 250 gms. per unmarried lady and 100 gms. per male member of the family, need not be seized.

(iii) The authorized officer may, having regard to the status of the family and the customs and practices of the community to which the family belongs and other circumstances of the case, decide to exclude a large quantity of jewellery and ornaments from seizure. This should be reported to the Director of Income-tax/Commissioner authorizing the search at the time of furnishing the search report.

(iv) In all cases, a detailed inventory of the jewellery and ornaments found must be prepared to be used for assessment purpose.

3. These guidelines may please be brought to the notice of all the officers in your region.”

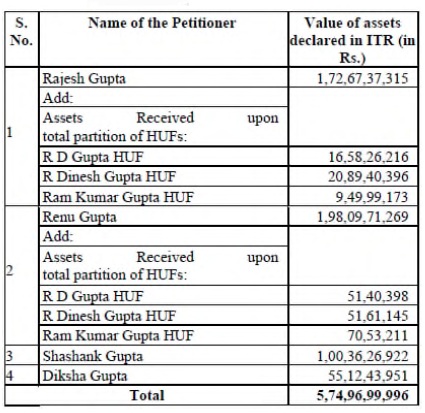

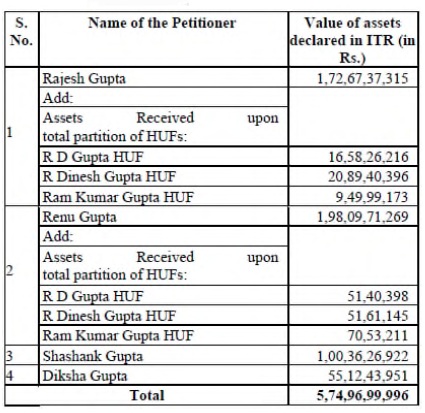

11. These instructions, she stated, are mandatory in nature and should have been strictly complied with. She also stated that the valuation of the jewellery under consideration is Rs.3.88 crore which is just one percent of the petitioners’ total disclosed wealth, which is Rs.574.97 crore. It is also her submission the Revenue has reproduced a truncated version of the table of the WTR of the petitioners whereby the disclosures in the hands of (i) RD Gupta, HUF; (ii) Dinesh Gupta; (iii) Shashank Gupta; (iv) Diksha Gupta, have been eliminated. Hence, the value of jewellery in their hands has been completely ignored. The petitioners have also placed before us their value of assets as disclosed by them, which according to them is squarely covered by the CBDT circular reproduced above. Details of the WTR for AY 2015-16, as placed on record by the petitioners are as follows:

12. As per Ms. Jha, the argument set forth by the counsel for the Revenue that there is a huge difference in the WTR for AY 2015-16 and the valuation report dated 29.06.2017, is without any application of mind. She submitted that the value of jewellery reported in the WTR is at the cost of acquisition and not at the market value. Given the fact that gold rates are rising exponentially on a yearly basis, the value of jewellery in the hands of the petitioners is carried forward on historical cost, the same is disclosed as shown in the hands of the HUF and the ones acquired by them have been disclosed at the time of the acquisition. Hence, the comparison of the WTR for AY 2015-16 with the valuation report is baseless and should not have been done.

13. She has challenged the reliability of the valuation report by the Revenue on various grounds. It is her submission that there is a lack of clarity about which rule or concept of converted weight has been adopted by the Revenue which can be seen from a bare perusal of the valuation report. She stressed that upon seeing item no.21 of the panchnama, the same would show that 2 tops having gross weight 10.100 gm and net weight of 8.500 gm was converted into converted gross weight of 742.45 gm and its value as such has been taken at more than 87 times the actual weight of the diamond top which is patently wrong on the face of it. The net weight of jewellery as per the valuation report of the jewellery seized is 2,519 gm only. She relied on this to say that the valuation report of the Revenue is not reliable.

14. She also stated that the petitioners have been clear and consistent about the fact that the methodology of valuation is erroneous. She denies the acceptance of this methodology by the petitioners and vehemently opposes it. As per her, the method of valuation adopted by the Revenue is alien to the valuation principle as well as the provisions of the Act. She further stated that it would be wrong to allege that the valuation report has been obtained after the date of search as the petitioners being a big family with various members and descendants conduct a valuation exercise on a routine basis, every 5-6 years.

15. It is her submission that the valuation report submitted by the petitioners dated 29.06.2017 was obtained by the petitioners from a government registered valuer under section 34AB of the Wealth Tax Act, 1957. This report provides all the necessary details such as name and address of the registered valuer, contact details, registration no. being CAT VIII-141 and hence, merely in the absence of the PAN of the valuer, this report cannot be brushed aside. Instead, Revenue should have conducted independent enquiries to test the authenticity of this report. As per her, the petitioners submitted all the available documents with the department before the lapse of the statutory time period of 120 days.

16. She stated the tone and tenure of the impugned order clearly demonstrates the preconceived notion and premeditated mindset of the Revenue to illegally withhold the jewellery/gold seized by them. It is her submission that petitioners never denied to provide the source of acquisition of the jewellery/gold and only stated that the same is not available with them at the moment and they would submit the same to the Revenue officials in due course. The Revenue has completely ignored the statutory provisions, the undertakings given before this Court and the directions of this Court, the same being evident from the manner in which the impugned order has been passed. Hence, the jewellery/gold has been illegally detained, merely because the receipts were not presented by the petitioners at the time of the search operation, and any outstanding demand against a family member does not justify blanket retention of all the assets by the Revenue.

17. It is also her submission that the impugned order on one hand records that the PANs of all the petitioners have been centralized to the office of respondent no.1, but on the other hand states that the assessment records of petitioners no.2 to 4 have not been received, in the absence of which the actual outstanding could not be ascertained. However, she stated the falsity in this statement is apparent from the fact that the outstanding liability of petitioner no.2 was relied upon for denying the request of release of jewellery. She stated this demonstrates that the record of petitioner no.2 was available.

18. She further stated that the respondent no.1 has pre-empted additions in the hands of the petitioners, which is completely inconsequential for the release of the jewellery/gold. As per her, respondent no.1 has chosen to seek invoices completely ignoring the fact that, as per the said instruction, the Revenue is only authorized to seize jewellery which is in excess of the gross weight declared in the WTR. Pertinently, it should be taken into consideration that the WTR and ITR do not mandate /prescribe itemized disclosure of jewellery or inventorising the wealth and only gross weight is to be declared. In light of the same, the petitioners valued the jewellery to substantiate the WTR/ITR.

19. As per her, the contention of the Revenue that the jewellery was seized in accordance with the CBDT instruction no.1916 dated 11.05.1994 is erroneous. She stated that there is no outstanding demand against the petitioners no.1,3 and 4, as on the date of search. After the introduction of data management on the ITBA Portal, the data pertaining to each and every assessee is available and accessible to the officers exercising jurisdiction over such assessees. Hence, the contention of the respondent that time was taken for transfer of assessment records to his office is nothing but a bald excuse which is required to be outrightly rejected.

20. She questioned how the records of the assessees had not been received by the officials when the impugned order itself mentions that the cases of these assessees have been centralized.

21. She also submitted that the respondents have alleged an outstanding demand of Rs.89,84,934/- against petitioner no.2 as per the order dated 18.03.2024, but the same disregards their own order dated 03.09.2025 under Section 154/143(3), wherein the said demand has been reduced to Rs.21,24,398/-. She stated this order of 18.03.2024 suffers from various mistakes which are apparent form the record. For this, the petitioner no. 2 moved an application for rectification under Section 154 of the Act. She further stated the petitioner no.2 is in appeal before the Commissioner of Income Tax (Appeals) [CIT(A)], which is pending disposal and as per the mandate of CBDT, when 20% of the disputed outstanding demand is paid, the remaining demand becomes irrecoverable. Hence, going by the record, the only tax liability is amounting to Rs. 21,24,398/- and that too is subject matter of appeal before the CIT(A).

22. As per her, the contention of the respondents show their malicious intent for securing the disputed outstanding amount of Rs.21,24,398/-. Once the demand is failed the outstanding balance is not payable during the pendency of such proceedings. Hence, it is illegal to recover the amount under the pretext of securing the Revenue’s interest.

23. It is her submission that the details of the dissolution of the HUF were duly placed on record before the Authorities and is part of the Revenue records. Further, the application dated 05.12.2024 for surrender/cancellation of PAN upon the complete dissolution of the HUF vide deed dated 16.11.2024 was also submitted to the Authority. She stated the Revenue had issued notices under Section 171 of the Act, to all the erst-while members of the HUF. These, were complied with, by all the petitioners. In light of these facts the challenge to the partition of the HUF is completely frivolous.

24. Ms. Jha has placed reliance on a decision of this Court in the case of Ajay Gupta v. CIT ITR 125 (Delhi) to substantiate her argument that as per Section 132B(1)(i), the jewellery should not have been retained after the lapse of 120 days. This Court held as under:

“9. In our opinion, the purpose of stipulating the period of 120 days cannot be over-emphasised. What the statute expects is that where a seizure has taken place consequent upon a search, the decision declining to release or return the amount to the assessee must be taken with extreme expedition. This is evidently how the department understood the provisions of the Income-tax Act since it has itself computed interest commencing from the expiry of the said period of 120 days, that is, 1-11-2002. Perhaps it would have been logical for Parliament to clarify that if a decision to hold or withhold monies/assets discovered during a search is not taken with the prescribed period of 120 days, interest would start to run from the date of the seizure itself. Otherwise, granting a blanket moratorium for the period of 120 days loses logicality…:”

25. She also drew our attention to the case of Mitaben R Shah v. Dy. CIT [SCA No. 10659 of 2009], of the Gujarat High Court to say that withholding of assets seized, beyond the period of 120 days is not tenable in law. Similarly, she also highlighted the decision in the case of Mul Chand Malu (HUF) v. Asstt. CIT ITR 46 (Gauhati), whereby, the Gauhati High Court held as under:

“8. The above quoted Section 132B was discussed and interpreted by a Division Bench of the Gujarat High Court in Mitaben R. Shah v. Dy. CIT [2011] 331 ITR 424. In that case, like in the case at hand, no decision was taken by the Revenue Department within 120 days from the date on which the last authorization for search under Section 132 was executed despite filing of an application within 30 days for release of seized assets. And the Revenue Department later dismissed the application for release of assets after the expiry of 120 days on numerous grounds. The Court held that when an application is made for the release of assets under first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act explaining the nature and source of the seized assets and if no dispute was raised during the permissible time of 120 days by the Revenue Department, it had no authority to retain the seized assets in view of the mandate contained in second proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. This decision does not seem to have been challenged by the Revenue Department before the Supreme Court. For the reasons stated in the decision, we too find ourselves in complete agreement with the view taken by the Division Bench of Gujarat High Court.

9. We accordingly allow the writ petition and direct the respondents to immediately release the seized assets of the petitioners.”

26. Reliance has also been placed by her on the following judgments:

| i. | | Kamlesh Gupta v. Union of India (Delhi)/W.P. (C) No. 2203/2021 (Del.) |

| ii. | | Nadim Dilip Bhai Panjvani v. ITO ITR 375 (Gujarat) |

| iii. | | Cowasjee Nusserwanji Dinshaw v. ITO [1987] 165 ITR 702 (Gujarat) |

27. Concluding her submissions, she stated that both the search and retention of the jewellery/gold are illegal, and the release of the jewellery does not warrant any bank guarantee at the behest of the petitioners as the Revenue has failed to make out any case against the petitioners. Hence, in light of her arguments, the writ deserves to be allowed and the jewellery/gold of the petitioners must be released.

28. Contesting these submissions, Mr. Sanjeev Menon, learned Junior Standing Counsel appearing on behalf of the respondents stated that the present writ petition is misconceived and untenable, both on facts and in law.

29. He stated that on 09.10.2024, the search and seizure operation was conducted on the residential and office premises of the petitioners. During the search, the following jewellery/gold were found and seized.

| Premise code | Premise Address | Owner of the jewellery & bullion | Jewellery & Bullion Found (value in INR) | Jewellery & Bullion Seized (value in INR) |

| B4R | House no.41, Street no.03, Shanti Niketan, Moti Bagh, Delhi-110021 (Residence) | Rajesh Gupta & Family | Rs. 5,39,76,316 | Rs.3,88,60,107 |

30. He stated that the jewellery/gold of the value mentioned above were found at the various premises including offices and residence during the search operation. The statement of Shashank Gupta, s/o Rajesh Gupta (petitioner no.3 herein), was recorded on 11.10.2024 under Section 132(4) of the Act. He stated that Shashank Gupta could not provide any justification or documentary evidence to substantiate the source of the purchase of the said jewellery/gold and therefore, in view of the CBDT instruction no.1916 of 11.05.1994, jewellery/gold worth Rs.3,88,60,107/- were seized, and the balance jewellery and gold were released.

31. He stated pursuant to the search the PANs of the Petitioners were centralized to Central Circle-31. The PAN of Rajesh Gupta was transferred from Central Circle-15, Delhi on 25.02.2025. The PAN of Mrs. Renu Gupta was transferred from Ward 28(1), Delhi, on 06.12.2024. The PAN of Shashank Gupta was transferred from Ward 28(1), Delhi, on 06.12.2024 and the PAN of Ms. Diksha Gupta was transferred from Ward 53(1), Delhi, on 25.01.2025.

32. He further stated appraisal report in the case of BDR Group was received in the office of answering respondent on 08.04.2025, while the seized material was handed over on 08.04.2025 & 05.05.2025. The assessment record in the case of Rajesh Gupta was received from Central Circle-15, Delhi on 16.04.2025. The assessment records in the case of Renu Gupta, Shashank Gupta & Diksha Gupta are still pending with the Jurisdictional Assessing Officer (JAO) and regarding these, requests have been made to Ward 28(1), 28(1) & 53(1), New Delhi.

33. He submitted that the first intimation regarding the release of jewellery was received vide an e-mail dated 23.01.2025, which had an attached application dated 25.11.2024, addressed to the Central Circle-17, New Delhi & Ward 28(1), New Delhi, which was the wrong address as the jurisdiction in the PAN of Rajesh Gupta was not Central Circle-17, New Delhi.

34. It is his submission the respondent no.1/Revenue duly complied with the Court order dated 07.07.2025 and in furtherance of the same passed the order dated 18.07.2025. It is his submission that the application for release of jewellery/gold was rejected on legitimate grounds and this decision was taken by the Revenue within one week’s time as instructed by this Court’s order, however, the order was digitally signed only on 18.07.2025. Hence, he submitted that no adverse view should be taken with respect to the passing of the impugned order. He further submitted that this application was dealt by the respondents in consonance with the CBDT instruction F.No. 299/06/2023-Dir (Inv-iii) dated 16.10.2023. It is a requirement under Section 132A that the release of any assets which have been seized can only be released after the nature and source of acquisition is explained to the satisfaction of the AO. This according to him, the assessee did not do. He stated that the assessee failed to provide any documentary evidence to satisfy the worth of the jewellery/gold amounting to Rs.3,88,60,107/-.

35. He further stated that there was already an outstanding demand of Rs.89,84,934/- against an order dated 18.03.2024 passed under Section 143(3) read with Section 144B reflecting against the PAN of Renu Gupta as per the ITBA demand portal, which was needed to be recovered as per CBDT instruction F.No.299/06/2023-Dir(Inv-iii) dated 16.10.2023. He also stated that only Rajesh Gupta’s assessment record was available with the answering respondent and apart from him, the records of other family members have not been received from the erstwhile jurisdictional assessee officer. Hence, without the proper assessment records, the actual outstanding demand against the petitioners cannot be ascertained.

36. To the contention that the search and seizure was illegal, Mr. Menon stated that at the time of the search proceedings, the assessee was not able to produce any bill/invoice/valuation report to justify that the jewellery was declared by them in their WTR. He also relied upon their WTR to state that no inventory of the jewellery/gold was mentioned therein. The assessee only mentioned the total amount representing the value of the jewellery held on the last day of the financial year in question.

37. It is also submitted by him that in terms of the settled principle of law under Section 132 of the Act, in the case of any person who is in possession of inter-alia, any gold (coins) or jewellery and such gold (coins) or jewellery represents either wholly or partly income or property which has not been disclosed, then in such case Revenue has the power to seize any such gold (coins) or jewellery, if found unexplained at the time of search. In light of the same, the contention that the search is illegal, as alleged by the assessees is devoid of any merit.

38. Mr. Menon also stated that the petitioners herein have questioned the methodology used during the valuation at the time of the search, however, this valuation was carried out at the premises of the petitioners and was accepted by them at that time. Therefore, it is now being questioned only as an afterthought.

39. Mr. Menon also placed before us the value of the jewellery declared by the petitioners in their WTR, based on the report received from Sanjiv Kumar Jain dated 31.03.2012, which we reproduce as under:-

| Sr. No. | Name of assessee | Value of jewellery declared in AY 2015-16 |

| 1 | Rajesh Gupta | 36,82,585 |

| 2 | Renu Gupta | 56,69,749 |

| 3 | Ram Kumar Gupta HUF | 34,92,460 |

40. He stated that for reconciliation of the jewellery which was seized in the search proceedings, the assessees have now produced the valuation report dated 29.06.2017. However, it cannot be relied upon. He challenged the authenticity of the report on the ground that it is well known fact that WTR has been abolished from AY 2016-17 and hence, the valuation of the jewellery/gold carried out on 29.06.2017 is inexplicable. Further, he stated that this report has been falsely prepared by the authority post the search operation by relying upon the Panchnama as it can be seen that all the items mentioned in the Panchnama have been reproduced in this valuation report. This report does not contain any identification like PAN, etc. of the valuer, hence, its veracity cannot be tested by the office. The falsity of this report can be further evidenced by the fact that the same was not produced before the competent authority at the time of the search proceedings and even during post-search investigations.

41. He stated that the petitioners have stated that some of the seized jewellery was received by them on their 25th wedding anniversary on 26.02.2018. However, they have included the same in the valuation report dated 29.06.2017 and shown it to be inherited by Renu Gupta from her late mother Smt. Angoori Devi on 20.08.2018 as ancestral wealth. This goes on to show the malafide on the part of the petitioners.

42. It is also his submission that when Shashank Gupta was questioned at the time of the search operation, it was stated by him that he would submit the bills/invoices for explaining the seized jewellery to the department within due course of time. However, nothing was done by him or the other assessees except providing a valuation report, which too does not explain how the assessee came to acquire such a huge amount of jewellery/gold.

43. He also stated that there is an unexplained jump in the valuation of jewellery in the possession of Rajesh Gupta and Renu Gupta for the AY 2015-16, the value of jewellery with Rajesh Gupta was Rs.36,82,585/- and with Renu Gupta was Rs.56,69,749/-, but on 29.06.2017, the jewellery in their possession amounted to Rs.3,05,42,663/-. No addition or documentary evidence has been provided by them to show that this income was coterminus to the income declared by them in their ITRs for the relevant AYs. He further stated that as per Schedule III of the Wealth Tax Act 1957 read with Section 7 of the same Act, the valuation being represented in the WTRs/ should represent the latest value of gold as on the valuation date. He also stated that in the absence of documentary evidence to show the purchase or inheritance of the jewellery, the same was lawfully seized by the Revenue

44. He stated that Renu Gupta also mentioned in the application for the release of the jewellery that she received jewellery worth Rs.1,67,94,003/-as a result of the oral partition between the members of the HUF on 01.10.2024, however, the same needs to be verified from the members of the HUF during the course of the assessment proceedings. Reliance was placed on the judgment in the case of Vineeta Sharma v. Rakesh Sharma [SLP (c) No. 8281 of 2020].

45. It is also his submission that the assessment in the group cases of the assessees is pending and on a prima facie perusal of the appraisal report, it is likely that the assessees have not declared all the income in their ITRs and some escapement of income is anticipated during the assessment, and only thereafter, the position of demand/liability of the assessees can be ascertained.

46. Mr. Menon stated that although Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act contemplates the release of assets, once the nature and source of their acquisition is wholly explained, however, the provision does not stipulate any automatic release. Only when all the conditions are fulfilled and a proper application is filed and an order recording that satisfaction is achieved, assets can be released. For this, a timeline of 120 days is provided on a non-imperative basis. The second proviso to Section 132B would only apply when the AO has concluded that the nature and source of acquisition has been explained by the person concerned, and has determined the liability of the assets, which is also the purpose behind this proviso. The same has not been done in the present case. A bare perusal of the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i), would show that the satisfaction of the AO regarding the nature and source of acquisition of the seized assets is a mandatory precondition for the exercise of powers to release the seized assets. The second proviso which prescribes the release of assets within 120 days from the last authorization of search, as per him, does not waive the requirement of the satisfaction of the AO with respect to the nature/source of the seized assets.

47. He submitted that it is settled law that a right created by a legal fiction is ordinarily the product of express legislation. The second proviso provides that the assets referred to in the first proviso i.e., the asset with respect to which the AO is satisfied about the nature and source of acquisition, is to be released within 120 days of the last authorization of search. However, the second proviso does not provide that on the expiry of 120 days, it would be deemed that the AO is satisfied about the nature and source of acquisition. In the absence of such a deemed satisfaction, such a legal fiction cannot be read into the provision in view of the aforesaid principle that a right created by a legal fiction is ordinarily, only a product of express legislation.

48. He stated that the expression “as is referred to in the first proviso” as against the words “assets seized under section 132” signifies the clear legislative intent of the second proviso to not be applicable to any seized material but only to the seized material with respect to which the conditions mentioned in the first proviso are fulfilled.

49. He has also referred to Section 132B(4) of the Act which provides for payment of interest on the seized items on the expiry of 120 days as provided in the second proviso to Section 132B(1)(i), and stated where the law provides for a certain consequence on the happening of an event, no other consequence can be read in. He has relied upon Notes of Clauses to the Finance Act, 2002, whereby Section 132B was first introduced, the relevant extract of which is reproduced as under:

“It is proposed to substitute section 132B to harmonise the provisions contained therein with the provisions for assessment in search cases laid down under Chapter XIV-B, and to further provide for release of assets seized during search and subsequently found to be explained to the satisfaction of the Assessing Officer, within a period of one hundred and twenty days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search under section 132 or for requisition under section 132A was executed. It is also proposed to reduce the rate at which interest is payable under sub-section (4) by the Central Government to eight per cent per annum. Such interest shall be payable for the period commencing on the expiry of one hundred and twenty days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search or for requisition was executed and ending on the date on which the assessment under Chapter XIVB is made.”

50. He has placed reliance on this note to state that the payment of interest under Section 132B(4) is tied up to the period of 120 days for the disposal of the application under the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i). The legislative intent is clear that on failing to pass an order under the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i), the only possible consequence is the payment of interest.

51. Reliance has been placed by him on the judgment in the case of Dipak Kumar Agarwal v. Assessing Officer ITR 419 (Allahabad)/2024: AHC 496500-DB wherein, it is held that the expiry of 120 days would not result in an automatic release of the seized items and the only consequence of failure to pass an order within 120 days is the payment of interest. The Court in Dipak Kumar Agarwal (supra) has considered the judgment of the Gujarat High Court in Mitaben R. Shah (supra), on which the petitioners have heavily relied. The relevant paragraphs are reproduced as under:

“29. Thus, the only consequence of non-compliance of Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act is by way of payment of interest at the highest rate provided by the legislature i.e. @ of 18 % per annum. The period for which such interest may become payable has also been specified under that provision. By imposing the levy of interest on the revenue, a plain reading of sub section (4) of Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act, the legislature itself contemplated cases where orders may remain to be passed by the Assessing Authority within the timeline provided under Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act. Payability of interest may arise only in a case where the order may have remained to be passed within a time stipulation provided under the second proviso to Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act. 30. That being the only consequence provided, we find it difficult to persuade ourselves to the reasoning of the Gujarat High Court in Mitaben R. Shah v. Deputy Commissioner of Income-Tax And Another (supra)-the sheet anchor of the submissions advanced by Senior Advocate for the petitioner, perusal of that decision reveals, mandatory intent was read into the language of Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act by relying on the reasoning/ratio in Cowasjee Nusserwanji Dinshaw v. Income Tax Officer : (1987) 165 ITR 702. That was a case of proceeding under Section 132 (8) of the Act and not Section 132 B of the Act, as it then existed.

***

31. On the test of consequences provided, Cowasjee Nusserwanji Dinshaw (supra) case was a different case altogether. It provided a statutory injunction against retention of books of accounts and other documents beyond a period of 180 days, unless reasons for their continued retention were recorded in writing with the approval of the Commissioner. In absence of reasons recorded and approval granted prior to the expiry of 180 days time limit, the seized books of accounts and documents had to be released.

32. Plainly that mandate of law does not exist under the provision of Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act. This provision only contemplates-a person subjected to search may not be made to wait endlessly for release of valuable assets that may have been seized during the course of search. If, the nature and source of acquisition of a seized asset is wholly explained and it may not be required for recovery of any outstanding demand or demand of tax that may arise under the assessment proposed to be made consequent to the search giving rise to the seizure itself, the same may be released. The provisions does not stipulate any consequence of automatic release. It would first have to be invoked by the assessee by filing a proper application. Then if conditions are fulfilled, an order recording that satisfaction may be passed. It is for that purpose a timeline of 120 days is contemplated on a nonimperative basis. In the event of delay in making the decision the revenue has been saddled with interest liability @ 18 % per annum. On the contrary under Section 132 (8) of the Act [as considered in Cowasjee Nusserwanji Dinshaw (supra)], a statutory duty was cast on the seizing authority to itself record reasons to detain seized documents beyond 180 days and the consequence of its non- adherence was also provided by way of release of the same. Therefore, in absence of statutory intent shown to exist, it may not be inferred through the process of legal reasoning-that if no order is passed within a time of 120 days, seized assets must be released notwithstanding its impact on the recovery of existing and likely demands.

33. As noted above, similar stipulations of time provided under different enactments have been interpreted to be directory and not mandatory. Therefore, we are unable to pursue ourselves to subscribe to the reasoning that has found its acceptance by the Gujarat High Court in the case of Mitaben R. Shah v. Deputy Commissioner of Income-Tax And Another (supra), Ashish Jayantilal Sanghavi v. Income-tax Officer (supra), Nadim Dilip Bhai Panjvani v. Income-tax Officer, Ward No.3 (supra) and Gauhati High Court in the case of Mul Chand Malu (HUF) v. Assistant/Deputy Commissioner of Income Tax (supra).

34. Insofar as, learned Senior Counsel for the petitioner has invoked the principle-if an Act is required to be done in a particular way, it may be done in that way or not at all, we find the same to be inapplicable to the present law. In our opinion, the provision in question [Section 132 B (1) (i)] being directory, the jurisdiction of the Assessing Authority to deal with the petitioner’s application dated 15.09.2022 did not lapse or abate upon expiry of the period of 120 days. Since that stipulation of law is only directory, it survives to the Assessing Authority to deal with the application, even today.

35. We may also observe at this stage, if on due application of mind, the Assessing Authority reaches a conclusion that the nature and source of Rs.36,12,000/- seized from Om Prakash Bind was duly explained and if assessing officer is adequately satisfied that that amount was neither required for satisfaction of any outstanding demand or satisfaction of demand that may arise pursuant to the assessment proposed to be made, such refundable amount would attract liability of interest under Section 132 B (4) of the Act read with Rule 119 A of the Rules.

36. In view of the above, we decline to issue the writ of Mandamus as prayed. Instead, we dispose of the writ petition with a direction on the Assessing Authority/respondent No.2 to proceed to deal with and decide the application of the petitioner dated 15.09.2022 within two weeks from today, by a reasoned and speaking order, after hearing the petitioner.”

52. This decision of the Allahabad High Court has echoed in the decision of Kanwaljeet Kaur v. Dy. DIT Kanwaljeet Kaur v. Dy. DIT [D.B. Civil Writ Petition No. 5706/2024, dated 21-8-2024]/2024:RJ-JP:35276-DB wherein the Rajasthan High Court has held as under:

“13. We are of the considered view that second proviso to Section 132B of the Act would apply only after the Assessing Officer has determined the liability and has come to the conclusion that the nature and source of acquisiton has been explained by the person concerned. In the present case, since the Assessing Officer has not decided the application, the second proviso to Section 132B of the Act would not come into play. We are of the considered view that the second proviso is mandatory, however, this will come into play only when the Assessing Officer has determined the liability. The purpose behind the proviso was that after determination of the liability, the assets and goods should not be retained by the department.

***

15. We are of the considered view that the judgment of the Allahabad High Court has dealt with Section 132B (4)(a) & (b) of the Act and has rightly come to the conclusion that the second proviso to Section 132B of the Act does not contemplate automatic release on expiry of 120 days”

53. It is his submission that the petitioners herein have tried to distinguish the judgment of Dipak Kumar Agarwal (supra) and Kanwaljeet Kaur (supra), however in these cases, unlike the present case, no order was passed under the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. The ratio of these judgments that the timeline of 120 days under the proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) is directory, is independent of whether or not an order was passed. He also contended that the Revenue/respondent in the present case stand on a better footing as the order rejecting the application of the petitioners has been passed by the AO, recording that he is not satisfied with the explanation of the assessee on the nature and source of acquisition of the seized assets.

54. He has placed reliance on the judgment in the case of P.T. Rajan v. T.P.M Sahir (2003) 8 SCC 498 and C. Bright v. District Collector (SC)/(2021) 2 SCC 392 to say that where a statutory functionary is asked to perform a statutory duty within the time prescribed, the same would be directory and not mandatory.

55. He submitted that although Section 132 B (1)(i) allows the assessee to seek release of the seized items, the decision taken by the AO under the first proviso is a tentative view on the satisfaction of the explanation provided by the assessee regarding the nature/source of acquisition of the seized asset. As per him the assessee does not suffer a final or determinative view as a result of the order and may still provide further explanation and supporting documents justifying the acquisition of the assets. If the AO is satisfied with the explanation provided by the assessee, he may release the seized assets, without availing the same for recovery against the existing liabilities and demands that may arise in the search assessment.

56. He also submitted that it is well-settled that judicial review under Article 226 is not directed against the decision but is confined to the decision-making process. To substantiate this, he relied upon the judgment in the case of Bachan Singh v. Union of India (2008) 9 SCC 161 and Union of India v. Rajendra Singh Kadyan (2000) 6 SCC 698.

57. It is his submission that the assessee has not provided any itemized details of the jewellery which was alleged to be either gifted or inherited by them. There is not a single averment anywhere explaining with respect to each item of jewellery, how it came to the possession of the petitioner herein. In the absence of the same, the AO was not in a position to arrive at a satisfaction and the same view taken by him cannot be faulted.

58. He stated that the petitioners have relied upon their wealth tax return to explain the acquisition of jewellery but the mere fact that jewellery may have formed part of the wealth tax returns of the assessee, itself does not explain the nature and source of acquisition of the jewellery and therefore, that by itself, does not meet the requirements of the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. Additionally, the AO has held in his impugned order at para 3 that the assessee was not able to produce any documentary evidence like bill/invoice/valuation report etc., to justify its claim that it is the same jewellery that was declared by the assessee in the WTR which was seized. Moreover, no inventory of the jewellery/gold was provided.

59. The petitioners have stated that they were not required to submit any inventory of the jewellery in their WTR, however, this submission is not legally tenable as Rule 18(2) of Schedule III of the Wealth Tax Act, 1957 requires assessees with wealth in the form of jewellery with value not exceeding Rs.5 Lakhs to have their return supported by a statement in the prescribed form, and where the value exceeds Rs.5 Lakhs to have their returns supported by a report of a registered valuer in the prescribed form. Rule 18(2) of the of Schedule III of the Wealth Tax Act, 1957 reads as follows:-

“(2) The return of net wealth furnished by the assessee shall be supported by,—

(i) a statement in the prescribed form, where the value of the jewellery on the valuation date does not exceed rupees five lakhs;

(ii) a report of a registered valuer in the prescribed form, where the value of the jewellery on the valuation date exceeds rupees five lakhs.”

60. As per him, the form of statement prescribed for Rule 18(2)(i) is Form O-8A, which requires the assessee to provide a list of each item of jewellery and provide a description of each item. The form of statement prescribed for Rule 18(2)(ii) is Form O-8. He relied on this to state that the jewellery belonging to an assessee is to be supported/accompanied by a Statement or a Report describing each item of jewellery, which must form part of the return of the assessee. Hence, this argument of the petitioners is devoid of any merit.

61. He submitted that the original application filed by the assessee on 25.11.2024 was accompanied by a valuation report dated 31.03.2012 but in this report, the assessee was not able to reconcile the jewellery seized with the disclosures made in the WTR. Subsequently, the petitioners filed another reminder letter dated 23.01.2025 accompanied by another Valuation Report dated 29.06.2015. The AO dealt with the same in detail in the impugned order. He stated that the Valuation Report by itself is not sufficient to prove the nature/source of acquisition of jewellery.

62. To the argument of the petitioners that the Memorandum of Dissolution of the HUF dated 16.11.2024 recording the oral partition was filed, Mr. Menon stated that this document has been executed a month after the search operation which was conducted on 09.10.2024 and in light of the same, the AO was justified in not readily accepting the plea of oral partition advanced by the petitioners, without verifying the same. For this, the AO had issued notices under Section 171 of the Act, however, no order under Section 171(3) has been passed.

63. Mr. Menon also stated that the petitioners have disputed the manner of valuation of the jewellery by the Revenue. However, he stated this in no way helps the assessee or precludes them from providing any information to justify the source of acquisition of the jewellery, which is the primary burden on them to meet in an application under the first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. Additionally, he also stated that this dispute with regard to the manner of valuation cannot be decided at the stage of the application under Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. He additionally submitted that it is a government registered valuer, who being an expert in this domain, has carried out the valuation. Hence, the authenticity of the report must only be disputed through a trial.

64. Concluding his submissions, Mr. Menon stated that in view of the averments made by him, the jewellery/gold must not be released till the finalization of the assessment proceedings. In any case, if the assessees want to seek the release of the jewellery/gold, then they may produce a bank guarantee before this Court as per the relevant CBDT guidelines.

Analysis

65. Having heard the learned counsel for the parties, the submissions of Ms. Jha can be summed up in the following manner:-

| (i) | | As per second proviso to Section 132B(1) (i) of the Act, it was incumbent upon the respondents to release the seized gold / jewellery within 120 days from the date of the search; |

| (ii) | | The date of search being 11.10.2024 and the application having been filed by the petitioners under Section 132B of the Act on 25.11.2024, the requirement of the first proviso to Section 132B(1) (i) of the Act has been met; |

| (iii) | | The impugned order was passed only on 18.07.2025, i.e. after 11 days of the date of order dated 07.07.2025 passed by this Court in W.P.(C) No.2938/2025 whereby the respondents have dismissed the application filed by the petitioners for the release of the jewellery / gold; |

| (iv) | | The petitioners are regular in filing their ITRs under the Act and during the search and seizure operation the petitioners have pointed out to the officers (a) WTR filed by the petitioners and earlier HUFs, (b) Jewellery Valuation Report; and (c) ITRs of the different AYs; |

| (v) | | The respondents have wrongly relied upon the CBDT instructions dated 16.10.2023 on the assumption that the instructions are applicable to future liabilities which may arise or may not arise pursuant to the assessment proceedings. As per paragraph 3 thereof the assets can be released if the AO is satisfied that the nature and source of this jewellery is explained; |

| (vi) | | The CBDT instructions dated 11.05.1994, more specifically paras (i) and (iii), are mandatory in nature and should be strictly complied with; |

| (vii) | | The respondents have ignored the valuation of the jewellery in the hands of the petitioners; |

| (viii) | | The value of the jewellery in the WTR and in the valuation report is at the cost of acquisition and not at the market value; |

| (ix) | | There is lack of clarity as to which rule or concept of conversion rate has been adopted by the Revenue. The valuation report submitted by a valuer dated 29.06.2017 was obtained by the petitioners from the registered valuer under Section 34AB of the Wealth Tax Act, 1965, which provides for all necessary details such as name, address of the registered valuer, contact details, registration number being CAT VIII-141, hence merely in the absence of the PAN of the valuer, the report cannot be brushed aside; |

| (x) | | The jewellery/gold cannot be illegally detained merely because of the receipts were not presented by the petitioners at the time of search operation; |

| (xi) | | The case of the respondent is of an alleged outstanding demand of Rs.89,84,934/- which is overlooking the order of the respondents dated 03.09.2025 under Section 154/143(3) of the Act wherein the said demand has been reduced to Rs.21,24,398/-; and |

| (xii) | | The retention of the jewellery is illegal and the release of the jewellery does not warrant any bank guarantee. |

66. At the outset, we intend to deal with the submission made by Ms. Jha that the time period of 120 days as prescribed under Section 132B(1) (i) of the Act is mandatory.

67. To answer this submission, it is necessary to reproduce Section 132B(1) (i) of the Act, which reads as under:-

132B. Application of seized or requisitioned assets.— (1) The assets seized under section 132 or requisitioned under section 132A may be dealt with in the following manner, namely :

(i) the amount of any existing liability under this Act, the Wealth- tax Act, 1957 (27 of 1957), the Expenditure-tax Act, 1987 (35 of 1987), the Gift-tax Act, 1958 (18 of 1958) and the Interest-tax Act, 1974 (45 of 1974), and the amount of the liability determined on completion of the assessment under section 153A and the assessment of the year relevant to the previous year in which search is initiated or requisition is made, or the amount of liability determined on completion of the assessment under Chapter XIV-B for the block period, as the case may be (including any penalty levied or interest payable in connection with such assessment) and in respect of which such person is in default or is deemed to be in default, or the amount of liability arising on an application made before the Settlement Commission under sub-section (1) of section 245C, may be recovered out of such assets :

Provided that where the person concerned makes an application to the Assessing Officer within thirty days from the end of the month in which the asset was seized, for release of asset and the nature and source of acquisition of any such asset is explained to the satisfaction of the Assessing Officer, the amount of any existing liability referred to in this clause may be recovered out of such asset and the remaining portion, if any, of the asset may be released, with the prior approval of the Principal Chief Commissioner or Chief Commissioner or Principal Commissioner or Commissioner, to the person from whose custody the assets were seized :

Provided further that such asset or any portion thereof as is referred to in the first proviso shall be released within a period of one hundred and twenty days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search under section 132 or for requisition under section 132A, as the case may be, was executed.

(ii) if the assets consist solely of money, or partly of money and partly of other assets, the Assessing Officer may apply such money in the discharge of the liabilities referred to in clause (i) and the assessee shall be discharged of such liability to the extent of the money so applied;

(iii) the assets other than money may also be applied for the discharge of any such liability referred to in clause (i) as remains undischarged and for this purpose such assets shall be deemed to be under distraint as if such distraint was effected by the Assessing Officer or, as the case may be, the Tax Recovery Officer under authorisation from the

Principal Chief Commissioner or Chief Commissioner or Principal Commissioner or Commissioner under sub-section (5) of section 226 and the Assessing Officer or, as the case may be, the Tax Recovery Officer may recover the amount of such liabilities by the sale of such assets and such sale shall be effected in the manner laid down in the Third Schedule.

(2) Nothing contained in sub-section (1) shall preclude the recovery of the amount of liabilities aforesaid by any other mode laid down in this Act.

(3) Any assets or proceeds thereof which remain after the liabilities referred to in clause (i) of subsection (1) are discharged shall be forthwith made over or paid to the persons from whose custody the assets were seized.

(4) (a) The Central Government shall pay simple interest at the rate of 3 one-half per cent for every month or part of a month on the amount by which the aggregate amount of money seized under section 132 or requisitioned under section 132A, as reduced by the amount of money, if any, released under the first proviso to clause (i) of sub-section (1), and of the proceeds, if any, of the assets sold towards the discharge of the existing liability referred to in clause (i) of sub-section (1), exceeds the aggregate of the amount required to meet the liabilities referred to in clause (i) of sub-section (1) of this section (b) Such interest shall run from the date immediately following the expiry of the period of one hundred and twenty days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search under section 132 or requisition under section 132A was executed to the date of completion of the assessment under section 153A or under Chapter XIVB.”

68. It may be stated here that Ms. Jha has relied upon the judgment in the case of Ajay Gupta (supra), more specifically on paragraphs no.7,9 & 11, which we reproduce as under:-

“7. In the present case, we are not concerned with this aspect of the statute since it is section 132B(4)(b) that is at the fulcrum of the conundrum. It clarifies that “interest shall run from the date immediately following the expiry of the period of one hundred and twenty days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search under section 132 or requisition under section 132A was executed to the date of completion of the assessment under section 153A or under Chapter XIV-B”. The period of 120 days (90 days up to September 30, 1984) was previously stipulated in section 132(5) of the Incometax Act until its omission by the Finance Act, 2002 with effect from June 1, 2002. Section 132(5) also prescribed that the remaining portion of the assets must be “forthwith released” to the person from whose custody they were seized after satisfaction of the tax liability existing against such person. At that time, i.e., prior to the amendments brought about by the Finance Act, 2002, section 132B(4)(b) envisaged payment of simple interest at the rate of 15 per cent. per annum on the retained money computed from the date immediately following the expiry of six months from the order under sub-section (5) of section 132. It is also worth emphasizing that seized assets for which a valid explanation has been furnished and which therefore do not partake of the nature of undisclosed income or assets cannot be retained even if there are outstanding tax dues.

***

9. In our opinion, the purpose of stipulating the period of 120 days cannot be over-emphasised. What the statute expects is that where a seizure has taken place consequent upon a search, the decision declining to release or return the amount to the assessee must be taken with extreme expedition. This is evidently how the Department understood the provisions of the Income-tax Act since it has itself computed interest commencing from the expiry of the said period of 120 days, that is, November 1, 2002. Perhaps it would have been logical for Parliament to clarify that if a decision to hold or withhold monies/assets discovered during a search is not taken within the prescribed period of 120 days, interest would start to run from the date of the seizure itself. Otherwise, granting a blanket moratorium for the period of 120 days loses logicality. This question has not been raised on behalf of the assessee and therefore we need not enter into an exercise of jural engineering to impart what, prima facie, appears to be a proper interpretation of the section.

***

11. Even though the rate of interest payable under section 132B(4)(a) and section 244A is the same since 2002 there was a difference prior thereto. This was obviously for the reason that Parliament considered search proceedings to be distinct from ordinary assessment proceedings. We have already observed that carrying out a search is an invasion of the privacy of a citizen. It is for good reason that the Income-tax Act imposes stringent safeguards and restrictions on the conduct of searches. For these very reasons, Parliament was mindful of setting down a comparatively short period of 120 days within which it expected summary proceedings relating to searches to be completed. In fact this period has been successively reduced by Parliament, since section 132B as originally inserted into the Act by the Income-tax (Amendment) Act, 1965 specified the period to be six months. This period was thereafter reduced to 120 days by virtue of the Finance Act, 2002. Obviously, Parliament is mindful of the fact that where assets and money belonging to a citizen are taken into custody by the Department consequent upon a search, a decision should be taken promptly as to what portion thereof is to be retained.”

69. Suffice it to state that the facts in the said judgment are clearly distinguishable in as much as the question which fell for consideration in that petition before this Court was the date from which the Income Tax Department is liable to pay interest on the amount of money /assets seized from the petitioner therein in the course of search conducted on 02.07.2002 under Section 132 of the Act. In the said case, the search was conducted on 02.07.2002, when an amount of Rs.35,15,000/- in cash was discovered at the premises of the petitioner, out of which, there was a seizure of Rs.33,00,000/-. It was the case of the department that during the block assessment proceedings, the assessee could sufficiently explain only part of the cash seized during the search. The block assessment proceedings were completed vide the assessment order dated 30.07.2004. According to the department, the assessee’s undisclosed income aggregating to Rs.12,43,232/- attracted a tax demand of Rs.7,83,236/- together with a penalty of Rs.7,83,236/- under Section 158BFA(2) of the Act, raising the total demand of Rs.15,66,471/- pursuant to the order. The balance amount Rs.17,33,529/- was released on 27.09.2004. Upon appeal against the assessment order, the CIT(A) vide its order dated 15.12.2004 deleted Rs.12,43,232/- as undisclosed income assessable to tax along with the penalty imposed. The AO gave effect to the order in appeal and framed nil income assessment on 24.12.2004, released the remaining amount of Rs.15,66,471/-. Thus, the entire seized amount of Rs.33,00,000/- was ordered to be released to the petitioner.

70. The question which arose before this Court was from which date the interest accrued to the petitioner. The claim of the petitioner therein was the payment of interest commencing from the expiry of the period of 120 days thereof, i.e. 01.11.2002. The department paid interest for the period 01.11.2002 to 30.07.2004, but failed to pay from 01.08.2004 to 27.09.2004. In paragraph no.9, the Court held as under:-

“9. In our opinion, the purpose of stipulating the period of 120 days cannot be over-emphasised. What the statute expects is that where a seizure has taken place consequent upon a search, the decision declining to release or return the amount to the assessee must be taken with extreme expedition. This is evidently how the Department understood the provisions of the Income-tax Act since it has itself computed interest commencing from the expiry of the said period of 120 days, that is, November 1, 2002. Perhaps it would have been logical for Parliament to clarify that if a decision to hold or withhold monies/assets discovered during a search is not taken within the prescribed period of 120 days, interest would start to run from the date of the seizure itself. Otherwise, granting a blanket moratorium for the period of 120 days loses logicality. This question has not been raised on behalf of the assessee and therefore we need not enter into an exercise of jural engineering to impart what, prima facie, appears to be a proper interpretation of the section.”

71. In paragraph 16 & 17, the Court further held as under:-

“16. As has already been noted above, computation of interest under section 132B(4) has been calculated with effect from November 1, 2002, on which there is no contest at all. The block assessment proceedings were completed in terms of the assessment order dated July 30, 2004, pursuant to which the sum of Rs.17,33,529 was returned on September 27, 2004. No appeal has been preferred by the Department on this score. So far as this sum of Rs.17,33,529 is concerned, interest under section 132B(4) became payable on July 30, 2004, which is the outer limit of the period prescribed under section 132B(4)(b). Since the payment was eventually made on September 27, 2004, the petitioner would be entitled to compensation on account of delay for the period August 1, 2004 to September 27, 2004. We direct that compensation/ damages, in terms of Sandvik Asia, be paid by the respondents to the petitioner on the sum of Rs.17,33,529 for the period August 1, 2004 to September 27, 2004, at the rate of nine per cent per annum.

***

17. So far as the sum of Rs.15,66,471 is concerned, the appeal was decided, (in favour of the petitioner), by the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) by orders dated December 15, 2004. The respondents are liable to pay interest on the said sum from November 1, 2002 to December 15, 2004, under section 132B(4)(b). The respondents have without any justification whatsoever paid only a sum of Rs. 31,328 as interest for the period September 1, 2004 to December 31, 2004, (the date of the Assessing Officer’s order is July 30, 2004) glossing over and ignoring the period November 1, 2002 to August 31, 2004 (It should be recalled that the assessment order was passed on July 30, 2004 and thus there is no plausible reason for tendering payment with effect from September 1, 2004). The respondents are accordingly directed to pay interest under section 132B(4)(b) on the said sum of Rs. 15,66,471 for the period November 1, 2002 to December 15, 2004, at the rate of 0.66 per cent. per month up to September 8, 2003, and thereafter at the rate of 0.5 per cent. per month. The question that arises is whether compensation/damages in Sandvik Asia Ltd. should be granted in respect of a sum of Rs.15,66,471 also. Since the decision of the Assessing Officer was reversed in appeal, there may not have been any justification for granting damages. However, since the period envisaged under section 132B(4)(b) specifically commences from the expiry of 120 days from the date on which the last of the authorisations for search was executed (which in the present case is November 1, 2002), the fact that interest has inexplicably been tendered only commencing from September 1, 2004, is indefensible. Therefore, in addition to payment of interest at the aforementioned rate, the petitioner shall also be entitled to receive from the respondent compensation/damages for the period November 1, 2002 to September 1, 2004, at the rate of nine per cent per annum.”

72. Hence, it is noted that the issue before the Court was not whether it is mandatory for the respondents to release the seized gold/jewellery within the period of 120 days of the search. So it follows that this Court in the aforesaid judgment had not considered the issue as to whether the period of 120 days under the second proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act has to be mandatorily adhered to and the jewellery / gold need to be released.

73. Similarly, in the case of Mitaben R Shah (supra) on which reliance has been placed by Ms Jha, the Gujarat High Court has dealt with the said provision and held as under:-

“20.In the above view of the matter, all these orders which are challenged in the present group of petitions retaining the assets beyond the period of 120 days are hereby quashed and set aside and the respondent authorities are directed to release the gold ornaments and jewellery seized by them during the course of search and seizure operation forthwith and in any case not latter than two weeks from the date of receipt of the writ of this Court or from that date of receipt of certified copy of this order, whichever is earlier.”

74. In the case of Mul Chand Malu (HUF) (supra) the Gauhati High Court has relied upon the decision of the Gujarat High Court in the case of Mitaben R Shah (supra) and held as under:-

“8. The above quoted Section 132B was discussed and interpreted by a Division Bench of the Gujarat High Court in Mitaben R. Shah v. Dy. CIT [2011] 331 ITR 424. In that case, like in the case at hand, no decision was taken by the Revenue Department within 120 days from the date on which the last authorization for search under Section 132 was executed despite filing of an application within 30 days for release of seized assets. And the Revenue Department later dismissed the application for release of assets after the expiry of 120 days on numerous grounds. The Court held that when an application is made for the release of assets under first proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act explaining the nature and source of the seized assets and if no dispute was raised during the permissible time of 120 days by the Revenue Department, it had no authority to retain the seized assets in view of the mandate contained in second proviso to Section 132B(1)(i) of the Act. This decision does not seem to have been challenged by the Revenue Department before the Supreme Court. For the reasons stated in the decision, we too find ourselves in complete agreement with the view taken by the Division Bench of Gujarat High Court.”

75. In Ashish Jayantilal Sanghavi v. ITO (Gujarat)/[2022] 444 ITR 457 (Gujarat) on which reliance has been placed by Ms. Jha, the Gujarat High Court while referring to the decisions in the case of Nadim Dilip Bhai Panjvani (supra) has held as under:-

“26. In view of the aforesaid, this writ application succeeds and is hereby allowed. The respondents are directed to hand over the seized asset (diamonds) to the writ applicant within a period of four weeks from the date of receipt of the writ of this order. It is needless to clarify that the assessment proceedings, if initiated against Parin N. Sheth with respect to the seized asset or even in the case of the writ applicant himself, may continue in accordance with law. Direct service is permitted.”

76. Per contra, Mr. Menon has relied upon the judgment of the Allahabad High Court in the case of Dipak Kumar Agarwal (supra) wherein the Court after considering the aforesaid judgments and position of law, has in paragraph no.20 onwards held as under:-

“20. Seen in that light, we come to the core issue involved in the present case. It is whether in such facts where the petitioner had made an application to release seized asset/cash of Rs.36,12,000/- in terms of the first proviso to Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act and the Assessing Authority failed to record any satisfaction within ‘120 days’ stipulated under the second proviso to the above noted provision, the petitioner became absolutely entitled in law to obtain release of those assets.

21. To decide that issue, we have to interpret the word ‘shall release’ appearing in the second proviso to Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act. If those words express mandatory intent, it cannot be denied that the petitioner would remain entitled to refund of Rs.36,12,000/-, upon the Assessing Authority’s failure to decide the petitioner’s application dated 15.09.2022 within the stipulated time of 120 days. On the other hand, if those words express directory intent, the application would survive for consideration by the Assessing Authority, in terms of first proviso to Section 132 B (1) (i) of the Act.

22. In grammar, the words ‘shall’ and ‘may’ indicate different intent. The word ‘shall’ is normally used to indicate to cause a mandatory effect whereas ‘may’ indicates action to be taken as per the doers volition. In usage, the difference may also indicate the degree of politeness invoked by the user. However in law though application of the rules of grammar is not excluded, at the same time interpretation in law as to mandatory or directory nature of the word ‘shall’ is not to be decided solely on the strength of rules of grammar. Well recognized principle in that regard involve looking at the object and purpose and whether consequences of non-compliance have been prescribed in law.

23. In State of U.P. v. Manbodhan Lal Srivastava: AIR 1957 SC 912, a five-Judge bench of the Supreme Court observed as below:

11. An examination of the terms of Article 320 shows that the word “shall” appears in almost every paragraph and every clause or sub-clause of that article. If it were held that the provisions of Article 320(3)(c) are mandatory in terms, the other clauses or subclauses of that article, will have to be equally held to be mandatory. If they are so held, any appointments made to the public services of the Union or a State, without observing strictly, the terms of these sub-clauses in clause (3) of Article 320, would adversely affect the person so appointed to a public service, without any fault on his part and without his having any say in the matter. This result could not have been contemplated by the makers of the Constitution. Hence, the use of the word “shall” in a statute, though generally taken in a mandatory sense, does not necessarily mean that in every case it shall have that effect, that is to say, that unless the words of the statute are punctiliously followed, the proceeding or the outcome of the proceeding, would be invalid. On the other hand, it is not always correct to say that where the word “may” has been used, the statute is only permissive or directory in the sense that noncompliance with those provisions will not render the proceeding invalid. In that connection, the following quotation from Crawford on Statutory Construction— Article 261 atp. 516, is pertinent: “The question as to whether a statute is mandatory or directory depends upon the intent of the legislature and not upon the language in which the intent is clothed. The meaning and intention of the legislature must govern, and these are to be ascertained, not only from the phraseology of the provision, but also by considering its nature, its design, and the consequences which would follow from construing it the one way or the other. ”

(emphasis supplied)

24. Then, in the case Banwarilal Agarwalla v. The State of Bihar And Others; AIR 1961 SC 849, another five Judge bench of the Supreme Court as under:

6. It was not disputed before us that when the Regulations were framed, no Board as required under Section 12 had been constituted, and so, necessarily there had been no reference to any Board as required under Section 59. The question raised is whether the omission to make such a reference makes the rules invalid. As has been recognised again and again by the courts, no general rule can be laid down for deciding whether any particular provision in a statute is mandatory, meaning thereby that non-observance thereof involves the consequence of invalidity or only directory, i.e., a direction the nonobservance of which does not entail the consequence of invalidity, whatever other consequences may occur. But in each case the court has to decide the legislative intent. Did the legislature intend in making the statutory provisions that nonobservance of this would entail invalidity or did it not? To decide this we have to consider not only the actual words used but the scheme of the statute, the intended benefit to public of what is enjoined by the provisions and the material danger to the public by the contravention of the same. In the present case we have to determine therefore on a consideration of all these matters whether the legislature intended that the provisions as regards the reference to the Mines Board could be contravened only on pain of invalidity of the regulation.”

(emphasis supplied)

25. Then, in C. Bright v. District Collector And Others; (2021) 2 SCC 392 a three Judge bench of the Supreme Court had the occasion to consider whether the word ‘shall’ used (in Section 14 of the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002) to prescribe 30-60 days time limit to deliver possession, was mandatory or directory. The Supreme Court considered the pre-existing law on the subject and observed as below:-

8. A well-settled rule of interpretation of the statutes is that the use of the word “shall” in a statute, does not necessarily mean that in every case it is mandatory that unless the words of the statute are literally followed, the proceeding or the outcome of the proceeding, would be invalid. It is not always correct to say that if the word “may” has been used, the statute is only permissive or directory in the sense that noncompliance with those provisions will not render the proceeding invalid and that when a statute uses the word “shall”, prima facie, it is mandatory, but the Court may ascertain the real intention of the legislature by carefully attending to the whole scope of the statute. The principle of literal construction of the statute alone in all circumstances without examining the context and scheme of the statute may not serve the purpose of the statute.

9. The question as to whether, a time-limit fixed for a public officer to perform a public duty is directory or mandatory has been examined earlier by the courts as well. A question arose before the Privy Council in respect of irregularities in the preliminary proceedings for constituting a jury panel. The Municipality was expected to revise the list of qualified persons but the jury was drawn from the old list as the Sheriff neglected to revise the same. It was in these circumstances, the decision of the jury drawn from the old list became the subject-matter of consideration by the Privy Council. It was thus held that it would cause greater public inconvenience if it were held that neglecting to observe the provisions of the statute made the verdicts of all juries taken from the list ipso facto null and void so that no jury trials could be held until a duly revised list had been prepared.

10. The Constitution Bench of this Court held that when the provisions of a statute relate to the performance of a public duty and the case is such that to hold acts done in neglect of this duty as null and void, would cause serious general inconvenience or injustice to persons who have no control over those entrusted with the duty, the practice of the courts should be to hold such provisions as directory. In a seven-Bench judgment, this Court was considering as to whether the power of the Returning Officer to reject ballot papers is mandatory or directory. The Court examined well-recognised rules of construction to observe that a statute should be construed as directory if it relates to the performance of public duties, or if the conditions prescribed therein have to be performed by persons other than those on whom the right is conferred.